Sadie Roe, whose true name is Maud Veach

/by Sophia Burns*

When the NY State Training School for Girls in Hudson, NY was closing in 1975, Karen DePyster, who was working there at the time, was asked to pack up old records in the basement. “I wasn’t sure what was going to happen to the records—would they all be destroyed? So I randomly took one,” she said.

Karen kept the record with her throughout the years. When she learned about the Prison Public Memory Project (PPMP), she remembered that she had kept the file in one of her file drawers, and wanted to “put it into the hands of somebody interested in it.” It was many years before she did that but in 2015, Karen donated the file to PPMP. In an interview on December 12, 2017, Karen commented that she had opened the file but never read it. “It’s a little file, I didn’t think much would be in there,” she remarked.

The file, a plain envelope tied up with a pink ribbon, contains institutional records from the House of Refuge for Women, in Hudson, NY, beginning in 1898. The majority of these records pertain to one young woman, “Sadie Roe whose real name is Maud Veach”, and chronicle Maud’s experience at this first reformatory for women in New York from the view of the institution’s staff.

Maud’s Story

Maud was incarcerated at the House of Refuge for Women from June of 1898 to November of 1899. At just sixteen years old, she was convicted of “common prostitution” and brought fifty miles from her home in Poughkeepsie, NY. Maud’s records reveal that while she was at the Refuge for Women, she was subjected to severe punishments and practices that today we recognize as torture. These records shed light on the conditions that other young women endured there.

After being incarcerated for nearly a year and a half, Maud’s conviction was overturned by Dutchess County Judge S.K. Phillips. In one letter to the Superintendent and the Matron at the House of Refuge, the Dutchess County court recorder wrote that “the punishment already inflicted upon the young girl [had] such a bearing that she would be better-behaved”. Maud’s story is a window into the ways young women experienced social stigma, sex work, incarceration, and reentry at a time when correctional facilities for women were only just emerging.

Childhood

Maud was born November 11th, 1881 in Wallkill, NY, a small hamlet in Orange County that is currently home to fewer than 3,000 residents. As a teenager, she lived in Poughkeepsie, NY with her parents, Walter and Delia Timmons Veach, older sister, Edith, and younger brother, George.

Her father worked in a paper mill, perhaps one of the two that were located in Poughkeepsie’s Upper Landing. Throughout Maud’s House of Refuge record, there is little mention of Maud’s mother, Delia, except that she was deemed “insane” after George’s birth.

Insanity, at this time, was a term used disproportionately to describe women: oftentimes, insanity was assigned to women for behaviors that were seen as violating their place in the home. Overexertion, death after the passing of a loved one, foul language, and epilepsy all fell under the umbrella of insanity, making it difficult to conclude what, exactly, Maud’s mother may have suffered. It is known that during this period women had few rights, and therefore had little to no voice in deciding to be treated: rather, these choices were made by husbands or brothers. Given the reference to George’s birth, it is possible that she may have suffered from postpartum depression. Charlotte Perkins Gilman wrote about her experience with this particular illness during the 1880s in the famous short story, “The Yellow Wallpaper.”

We do not know much else about Delia Veach, but we do know other adult women supported her daughter. With the help of her maternal aunt, Maud attended parochial school in Kingston. The years in which she attended are unknown, but she may not have attended the school for long: according to her record, she could only read at a third grade level.

Staff at the House of Refuge wrote that Maude had “limited natural mental capability,” which could signify a disability. If she was considered to have a developmental disability, this could explain why she received such little education. It is unlikely that schools at the time could accommodate differing levels of ability, and her family may not have seen education as being worthwhile for her. Maud’s perceived disability could have also made her more vulnerable to being drawn into sex work. While Maud could have entered into this work voluntarily she could, instead, have been preyed upon by those seeking to make a profit off of prostitution. The vague assessment of Maude’s “mental capability” obscures what exactly she struggled with but it does show that disability may have played a role in her experience in society and at the House of Refuge.

In Poughkeepsie, then a bustling and wealthy city, Maud was employed as a domestic “upstairs girl.” Domestic labor was one of the few sectors in which women were employed during this period, especially those with minimal education. In a 1912 editorial in Ladies’ Home Journal entitled “It Works Like a Charm: Scientific Management and the Servant Problem,” the author wrote, “there is more danger of prostitution for the girl in domestic service than in any other occupation.” While a direct relationship between Maud’s domestic work and her involvement in prostitution is unclear, the records in her House of Refuge file note that she was employed until she “got in bad company,” which may suggest that she was fired from her post because of these activities.

When Maud was admitted to the House of Refuge, she was given the identification number “916.” At the New York State Archives in Albany, NY in the “General Record of Prisoners committed to the House of Refuge for Women, Hudson, N.Y.”, the majority of girls admitted around the same time as Maud were also domestic workers.

Maud may have assumed some financial responsibility for her family, given that her mother was incapacitated and her older sister was married. Some historians also find that women who were domestic workers looked to prostitution for a sense of freedom and independence that working in the home did not provide. While we do not presently know how she became involved in sex work we do know that she assumed an alias. Many of her records refer to her as “Sadie Roe, whose true name is Maud Veach.”

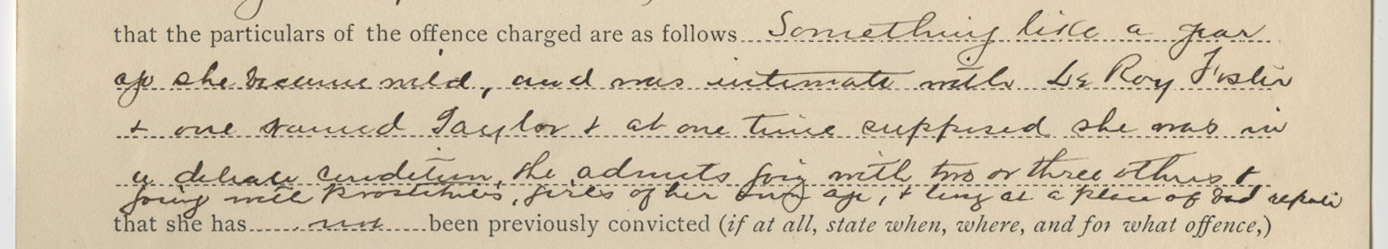

On June 4th, 1898, Maude was charged with “being a common prostitute and frequenting disorderly places and houses, [and] indecently exposing herself.” She was 16 years old. There was no coverage of Maude’s case in the Poughkeepsie Eagle, the local newspaper at that time, but it is apparent from other articles published at the time that “common prostitution” was a common occurrence.

The women mentioned in these articles were sent to a number of different facilities, including St. Anne’s Home in Albany, NY and the Bedford Home in Westchester County. While we cannot know her family’s reaction to her sentence, the opinion appears to have been that incarcerating young girls would by nature rehabilitate them. In 1908, the Poughkeepsie Eagle reported on the case of Ada van de Mark, and her father commented that he was unaware of her involvement in sex work and thought “the confinement will do her much good.”

Incarceration

Maud’s intake record listed her as having low “moral susceptibility,” reflecting the belief that prostitution was the result of moral failure that could be altered through “isolation.” Whether or not isolation was instituted in the interest of the women or society at large is unclear. However, the fact that her “moral susceptibility” is included in her record speaks volumes about what the court hoped to accomplish with her sentence. Like Maud, most women who were imprisoned during this era were not convicted of violent crimes, but rather ones of morality, including “prostitution, ‘lewd behavior,’ and vagrancy.”

This also relates to the perceptions of Maud’s possible disability. “Feeble-minded” women were seen as threats to society for a number of reasons. One 1909 paper in the Journal of Psycho-Asthenics claimed that “Feeble-minded women are almost invariably immoral...” Morality and ability had a close relationship during this period, and the House of Refuge clearly took the two into close account when receiving young women.

Maud’s House of Refuge file is heavily populated with written comments on her behavior supplementing the numerical ratings of her “honesty,” “personal cleanliness,” “destructiveness,” and the like. Earlier behavior records during the summer months in 1898 reflect high average scores and sparse written comments, noting profanity and “insolence” toward officials. The records do not show that Maud was punished or sanctioned for this behavior.

However, once September began, these notes grow dense and more detailed, revealing a dark turn in Maude’s experience at the House of Refuge. Profanity and disagreeability were, again, regularly cited. There are also several comments about her speaking during silent times, such as after the nighttime bell, at the dinner table, and during church services. She was removed from school for talking and “indolence.”

During October of 1898, Maude received a most severe punishment. An entry reads, “Shower bath – Dungeon – haircut,” with no context of what exactly she was being punished for. The shower bath is known to have been used in New York State, with graphic records from a 1858 article in Harper’s Weekly made available online by the New York Correction History Society.

The torturous practice was said to be used for convicted felons, and was described in Harper’s as if it were a spectacular phenomenon: “We need no longer, it seems, travel to China or Japan for illustrations of torture. A visit to our own penitentiaries and prisons will furnish all the horrors that the most curious appetite can desire.“

Punishment appears to be overtaking the rehabilitative focus emphasized and lauded in penitentiaries of this era. Only certain types of corporal punishment appear to have been accepted however. When whipping was banned in New York prisons in or around 1845, the shower bath remained in several state facilities, and took on varying forms across institutions.

The goal of the shower bath was submission, and appears to have been used on those who were deemed resistant, belligerent, or in any way threatening. An African-American man held at Auburn State Prison was killed by the shower bath, which virtually drowned him in freezing water for thirty minutes. While Maud survived, these accounts illuminate the horrific nature of this form of punishment, as well as the violence she endured for minor infractions of institutional rules.

Other punishments Maud endured in 1898 included “Taken to the punishment floor” for talking at the table, and “locked in for raking bread from [the] table.” Evidently, isolation within the facility was used profusely on Maud, who was just 17 as of that November. This raises questions about what exactly the “punishment floor” was at the House of Refuge, which is clearly distinguished from the dungeons. It may have been what a NYC newspaper article referred to in 1901 as the ‘light room’ and the ‘white room’, another practice today deemed to be torture.

This NYC newspaper article, described in a Hudson Register article in 1901, and reported on by local Hudson history detective and blogger, Carol Osterink, quotes a former resident of the Refuge who describes this room and what went on there as follows: “The white room is a bad torture. It is a room the size of an ordinary cell and is painted white with a glass ceiling like a hothouse. The girls are put in there upon the least provocation. If one breaks a dish or anything there by accident she is confined in this room. The first day or two, she is handcuffed to the floor so all she can do is to lie down, or sit up. She is fed on bread and water for a day or two and then has soup and bread until the end of the first week, when she has the regular meals again, but those are so coarse that many times the girls cannot eat them for several days at a time. I have helped carry girls from the light room after they have gone out of their heads and later had brain fever. Four who received this treatment were sent to Mattewan to the state hospital while I was at Hudson. At night, bright electric lights are turned on and the girls have to endure them all night. Few can stay in this room without having fearful headaches and going out of their minds. “

In Maud’s case, it appears both the ‘light’ and ‘dark’ rooms as well as her own quarters were used to contain and segregate her from the rest of the girls.

According to the Visitors Log from the House of Refuge, Maud received a host of visitors on November 10th, 1899. This was only the second instance in which loved ones visited her, the first of which was a visit from her sister and brother in October. The November visit involved both of her siblings; a judge (The Honorable Fulton Paul); a minister (Rev. Chas. Park); and three women whose connections to Maud are unknown.

The day before Maud’s November 10th visitors arrived, a letter had been sent from an attorney, S.H. Brown, to the superintendent and matron notifying them that Maude’s sister would be retrieving her from the House of Refuge. In the letter, Brown writes, “Mrs. Hayes is an eminently respectable woman here and I think that the punishment already inflicted upon the young girl will have such a bearing that I think she will have no great trouble with her.”

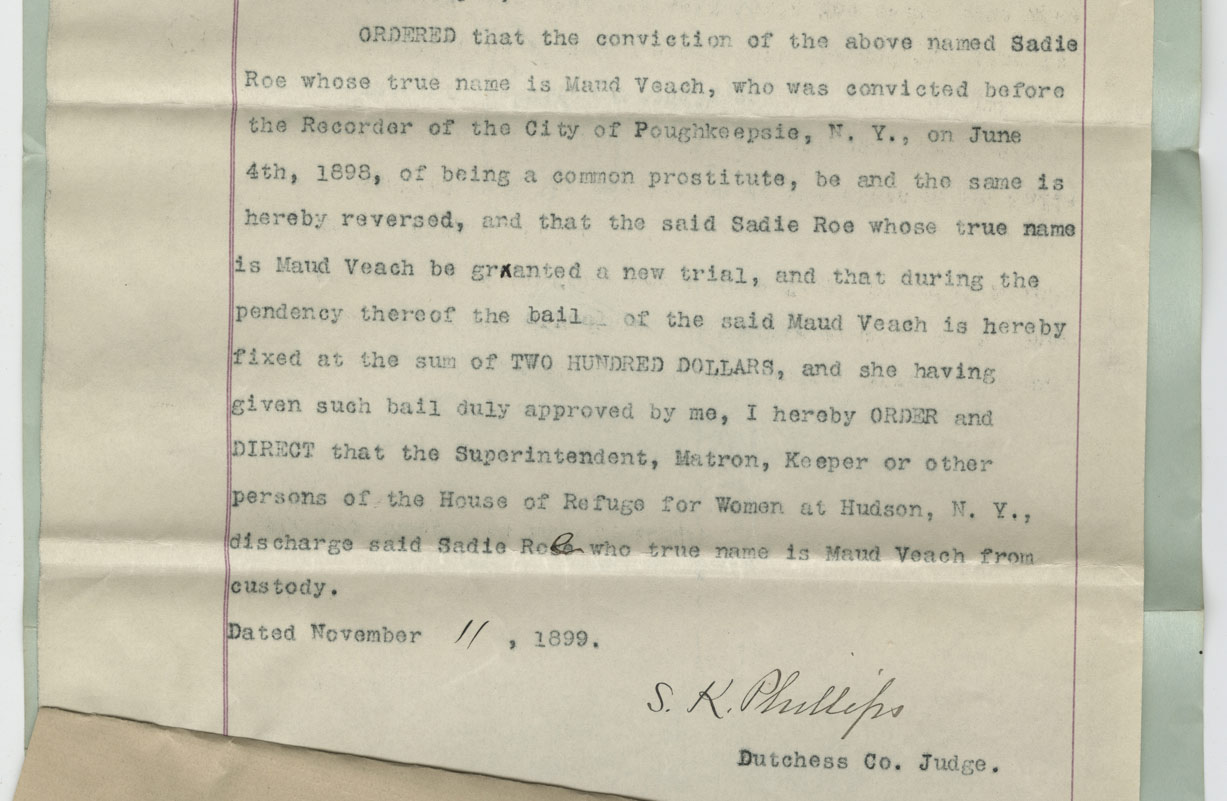

The reversal of Maud’s conviction by the Dutchess County Judge, S.K. Phillips, is recorded in a document dated November 11th: “The People vs. Sadie Roe whose true name is Maud Veach.” Her bail was fixed at $200, equivalent to $5,634 in 2017. While Maude’s file does not include release documents, it may be assumed based on the November 9th letter that Maude was released to her sister Edith.

Re-entry and later life

We found very little evidence of Maud’s life after her incarceration. From one article in the Poughkeepsie Eagle News, dated April 30th, 1901, we learn that a young man, George Abeel, apologized to Maud in open court for sending her a letter via mail using “disgraceful language.” While the nature of this letter is unknown, there could potentially be a link between Abeel’s harassment of Maud and her incarceration or her involvement in sex work. Despite these events, Maude remained in Poughkeepsie and married a man named Edward Burlingame, passing away on March 31st, 1947 due to a prolonged illness. She was survived by her three daughters and her brother George, and was laid to rest in her home city, Poughkeepsie.

Further Reading

Ryan Reft, “An Age of Agency: Working Women's Role in Leisure, Treating, and Prostitution 1880-1945,” 12 June 2012, Web, http://videri.org/index.php?title=An_Age_of_Agency:_Working_Women%27s_Role_in_Leisure,_Treating,_and_Prostitution_1880-1945.

Acknowledgments

A special thanks to Kira Thompson, local history librarian at the Poughkeepsie Public Library, for extending her talents to help locate relevant articles in the Poughkeepsie Eagle newspaper and to Karen DePeyster for sharing her story on finding the file containing Maud Veach’s records from the House of Refuge for Women.

*Sophia Burns was a 2017 intern with the Prison Public Memory Project in Hudson, NY. An Urban Studies major at Vassar College, she graduated in May, 2018. Her work with the Project involved primary source investigation, interviewing, historical research and writing this article.