When The Gates Are Closed

/By Brian Buckley

In a post on our website in 2014, PPMP contributor Russ Immarigeon wrote about the closure of the New York State Training School for Girls in Hudson, NY through the perspective offered by the local Hudson newspaper’s coverage of the closure. During 2015-2016, Brian Buckley, former PPMP Hudson Site Coordinator, received a Larry J. Hackman Research Residency Award from the New York State Archives to further research the story of the Training School’s closure, this time as told by the letters, reports, and memos sent and received by the offices of Governors Nelson Rockefeller and Hugh Carey (1971-1975), whose tenures overlapped with the events surrounding the School’s closure.

For more information about the New York State Archives and the Hackman Research Residency Program, please visit the following links: NYS Archives, Larry J. Hackman Research Residency.

Gates to the New York State Training School for Girls from Worth Avenue. Source: Peter Tenerowicz.

In the summer of 1975, the future of the New York State Training School For Girls in Hudson, NY was up in the air. The state was struggling to curb spending during one of its worst fiscal crises and the Training School was one of many large, state-run institutions on the chopping block. Meanwhile, the town of Hudson fought the closure. More than 5,000 Hudson residents signed a petition to then Governor Hugh Carey urging him to keep the facility open:

During these difficult times, when many communities oppose correctional type facilities in their areas, the desires of the Hudson area community should be a main point of consideration. The Training School has been in Hudson over seventy years and has become an integral part of our community.

Eliminating Institutions

Due in part to its age, the Training School had been on the radar for possible closure long before 1975. According to the letters of Governor Nelson Rockefeller, the closure had been in the works as early as 1971, when a letter from the Governor’s office reported, “The closing of this facility is under consideration and probably will be accomplished… The age and condition of the buildings and the unstable soil conditions at Hudson are such that reconstruction would be so expensive as to dictate the necessity of exploring alternatives.”

The man then tasked with planning the closure of the Girls’ Training School was the School’s superintendent, Thomas Tunney. In a letter a few years later, Tunney wrote, “During my entire adult life, I have been involved in institutional work with adults and juveniles and my efforts have been toward eliminating institutions as much as possible while attempting to introduce modern, innovative, treatment-oriented methods. Toward this end, early in 1971, I authored the Hudson ‘five year phase-out plan’.”

Tunney devised the Training School’s phase-out plan during a national trend away from large, state-run juvenile institutions and toward smaller, community-based group homes and rehabilitation centers that touted more personalized care and closer proximity to the young people’s homes. Moreover, the New York State Division for Youth (DFY) that managed the state’s juvenile prison system had commissioned a study finding that the Training School needed costly repairs to its outdated physical plant and that the institution’s per-capita operating costs were the highest of all the state training schools, with an annual budget of $21,000 per resident. The study reported that the training school system as a whole had much higher per capita costs than the smaller, residential facilities that, according to DFY, offered a “preferred treatment environment.”

A Financial Loss

In January of 1975, Hudson’s Save Our School (SOS) Committee commissioned its own study to counter these claims and convince the state to keep the Training School open. The Committee argued that the higher per capita costs reflected the School’s superior services. The study reported, “It is the Hudson Training School that provides the second largest amount of psychiatric care, the most psychologist’s time, and the most social services attention to each child—overall, the most treatment services of any of the training schools.”

The SOS report also claimed that, because the Training School had a larger number of black staff members, it was better prepared than other facilities to care for girls of color. “The training schools have a large minority population,” the study said, “Hudson School has 50% black students and 50% black staff, the largest proportion of black staff in the training school system. Many of these staff would be lost in a relocation effort.”

New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller. Source: Brittanica.com

But the main issue that those opposed to the closure raised was the economic impact on the Training School’s host town of Hudson. “The loss of the School for Girls to this community would be the equivalent of the loss of a major industry,” wrote Hudson’s mayor, Elmer Scheffer, in a 1973 letter to Governor Rockefeller. “Much of the annual budget of nearly two million dollars is spent right here, and the School personnel have their homes here and spend most of their salaries here. We are not an affluent area as your Department of Commerce knows; such a financial loss would be a major catastrophe.”

These concerns were compounded by the fact that annual state aid to Hudson had recently been cut by nearly $130,000 and the town had just lost one of its other major employers, a cement plant.

The Training School's final superintendent, George Dolecal (right), fields questions from reporters about the School's possible closure. Source: Hudson Register-Star, August 11, 1975.

Allegations of Abusive Treatment

The economic impact of closing the Training School was not the only topic of debate about Hudson. In November 1974, the Children’s Services Bureau of the Board of Social Welfare (BSW) received a letter from Training School social worker Sylvia Honig. The letter contained, in the words of the Bureau, “allegations of abusive treatment of the [Training School] residents: of inadequate medical treatment, treatment procedures, educational and recreational programming, and of inappropriate disciplinary measures taken toward the residents.”

A month after they received Honig’s letter, a staff team from BSW visited the Training School to investigate the allegations. In addition to general allegations, including “that medication was being dispensed to the residents in a haphazard manner” and that “there has been and continues to be inadequate administrative direction and supervision of the overall program at the Hudson School,” BSW also investigated a number of more specific allegations, including “that on June 5, 1974 … a resident of Cottage 12 had been punched in the eye by … a male child care worker,” “that on August 14, 1974 … a resident of Cottage 12 was forcibly undressed in the isolation room of the multi-purpose unit by three male and one female staff,” and “that a nurse at the Hudson School had refused to provide emergency room treatment at a local hospital to … a resident of Cottage D who was experiencing a severe asthma attack.” The report described each of these incidents in detail and made recommendations for “prompt corrective action” to the director of DFY, Milton Luger.

On behalf of DFY, Luger commissioned his own investigation. The report read:

Our investigation, including a full report by the Superintendent, substantiates your finding in that the incidents did happen in substance. However, it must be pointed out that a conflict has and does exist with Miss Honig towards the Hudson administration… As you are aware from your own institutional experience, incidents are frequently subject to a variety of interpretations.

Luger wrote his defense of the Hudson Training School’s treatment practices to BSW on February 10, 1975. Four days later, Honig testified before the New York State Assembly about the conditions at the Hudson Training School and the New York Times picked up the story. Within weeks, a meeting was held between representatives of the Governor’s office, BSW, and DFY to discuss the allegations. After the meeting, Bernard Shapiro, Director of BSW concluded that although he would send one social welfare staff member to Hudson “to spend at least one day reviewing the progress that they say has been achieved since we released the report,” he would not proceed with BSW’s investigation. He wrote, “We feel that overall [the Division for Youth’s follow-up report] is a satisfactory report considering the present circumstances at Hudson, i.e., the potential closing of the school.”

Fiscal, Programmatic, Human, and Political Decisions

Facing one of the worst fiscal crises in New York State history, Democrat Governor Hugh Carey submitted his 1975-1976 Executive Budget to a divided state legislature in the early weeks of 1975. He included in it another year of funding for the Hudson Training School, explaining in a letter to a representative from Hudson’s district that he hoped the funding would buy some time “to fully explore the impact of closing the school prior to making a final decision as to its future.” But in their amendments to the Executive Budget, the state legislature that year ratified a version of the budget that only funded the Girls’ Training School for half the year, effectively phasing it out.

Save Our School rally in Hudson, NY. Source: Hudson Register-Star, May 16, 1975.

The SOS Committee mobilized, large rallies were held, and local and state politicians spoke out against the potential closure. Within weeks the Governors’ office received countless letters urging his office to negotiate at least another full year’s funding for the Training School. Richard Hegner, a senior policy analyst in the Governor’s office, responded to the mixed messages surrounding the School’s closure in a memo:

The hesitation on this matter is uncalled for and is putting the Governor in an embarrassing position. An aura of indecisiveness surrounds the Hudson School closing. We have a legitimate excuse for closing it now—namely, despite the fact the Governor requested funds in the Executive Budget, the Legislature decided to force a phaseout of Hudson by approving funding for only a limited portion of the year at Hudson. Moreover, the district is traditionally Republican.

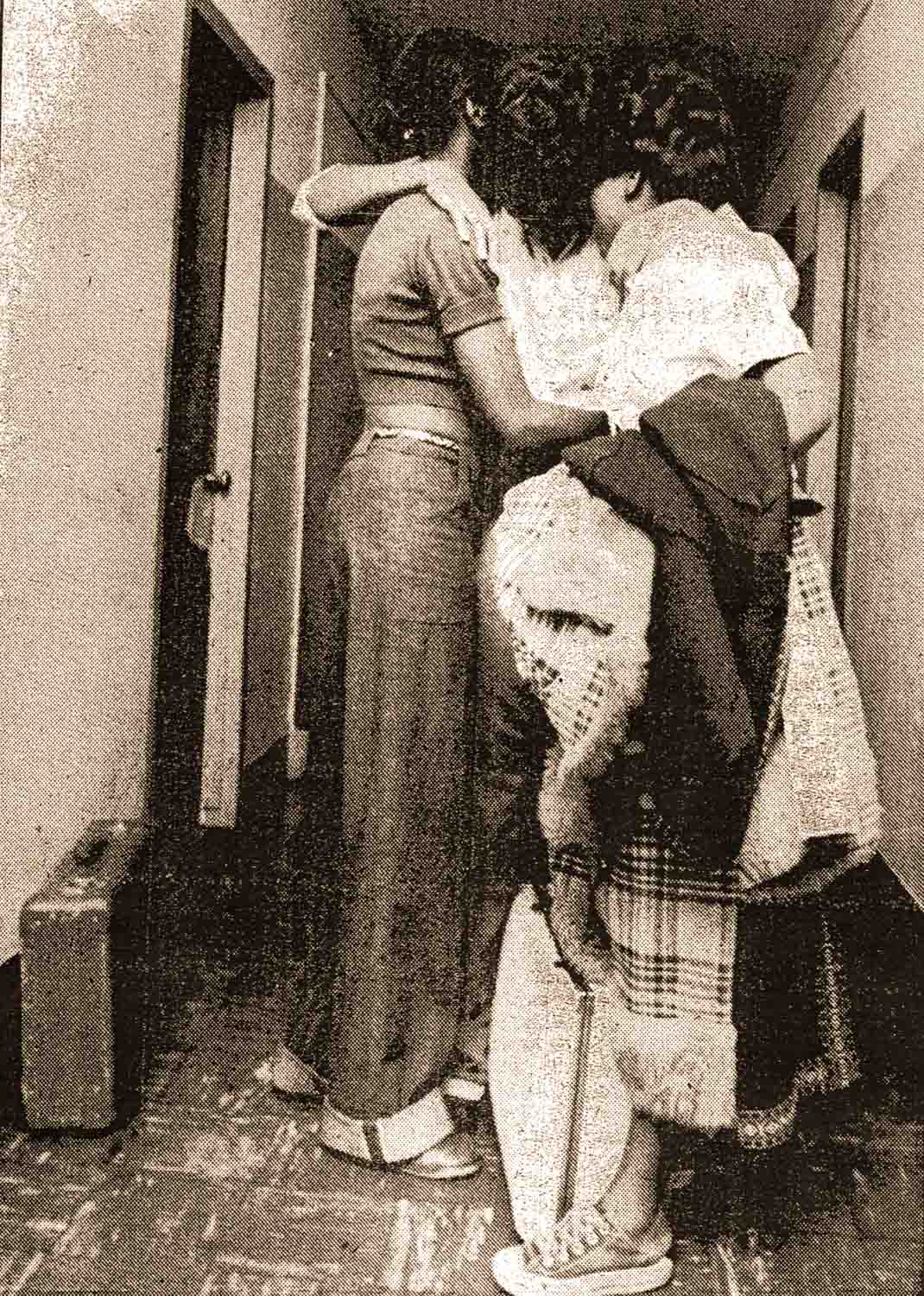

Girls' Training School residents packing their belongings. Source: Hudson Register-Star, August 19, 1975.

On August 15, 1975, DFY ordered the Training School closed. Some of the staff would be ‘bumped’ to positions at other DFY facilities, while others would be let go. Some of the nearly 70 residents still at the School were transferred to other juvenile institutions. Over half of the girls were released back to their homes. As girls packed their bags and staff cleaned out their desks, the local newspaper was there to cover the story. “The tearful good-byes, cleaning up, and job placements will continue at least for a little while,” the Hudson Register-Star reported, “But no one doubts that the end is approaching. The years of uncertainty and the State Training School in Hudson are finished.”

Training School staff saying goodbye. Source: Hudson Register-Star, August 19, 1975.

Locksmith John Drabick locks the Hudson Training School administration building for the last time. Source: Hudson Register-Star, September 11, 1975.