A Very Good Girl: The Lillie Patch Case File

/By Emma Friedlander

Although hundreds of young women were incarcerated at the House of Refuge for Women in Hudson, New York from 1887 until its closure in 1904, we know of only two complete case files from the period. These rare folders contain the institution’s educational, social, and medical records on a particular resident. A friend of the Prison Public Memory Project shared with us one of these case files, the Lillie Patch case file, only last year. Our friend received the file from Tom Davies[1], a former social worker at Brookwood Secure Center who held onto the folder for over 30 years. The thick folder tells one girl’s story in unusual depth, revealing a rich and complicated history.

Finding the File

In 1975, the New York State Training School for Girls in Hudson permanently closed it doors. The storage areas were cleaned out to make room for the new Hudson Correctional Facility, a medium security state prison that would house adult males. In a storage unit in the basement of the infirmary, along with GI rations from World War II, was discovered the Lillie Patch case file, an unusually complete document from 80 years prior when the buildings belonged to the New York House of Refuge for Women.

“I was working at Brookwood [Secure Center] at the time,” said Davies, who came into possession of the file shortly after its discovery. “Someone told me they found these old files, and I said ‘Geez, I’d like to see them.’”

A social worker specializing in juvenile delinquency, Davies recognized the file as a rare window into earlier juvenile reform practices. Moreover, Brookwood’s connection to the Hudson facility intensified Davies’ interest in finding out what happened on the grounds all those years before.

Brookwood Secure Center, opened in 1964[2], is a juvenile male correctional facility in Claverack, New York, just southeast of Hudson. The buildings that housed Brookwood were originally built as an annex of the Training School For Girls containing farmland for vocational programming and its disciplinary building, out of the way from the main institution in Hudson.

“When Hudson closed, many of the employees came over to work at Brookwood, which was at the time considered an annex of the Hudson Training School,” Davies explained. “Part of [the Hudson annex] was the old farmstead, and Brookwood was built on that land. Across the street from Brookwood were the housing units, which at one time, I was told, were where some of the girls from the Training School lived with house parents to take care of the farm animals.”

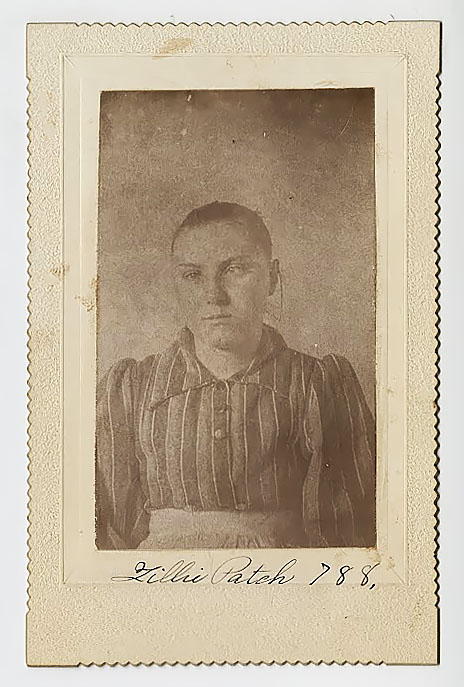

Davies was immediately struck by the case file’s details on the criminal and juvenile justice system at the turn of the twentieth century. The file comprises a wide variety of document types, including commitment records, behavioral reports, letters, photo portraits, and an application for transfer to the State Custodial Asylum for Feeble-Minded Women. By sorting through these different primary sources we may form an idea of one girl’s experience at the House of Refuge for Women, and how this individual experience reflects broader social trends of the time.

“Vagrancy in that she is a common prostitute”

Lillie Patch was born in 1878 in Saratoga Springs, New York. Her record of conviction reveals that on November 19, 1896 she was sentenced by the Saratoga Springs County Court to five years at the House of Refuge for Women on the charge of “vagrancy in that she is a common prostitute.”

Opened in 1887, the House of Refuge for Women was the third reformatory for women in the United States and, at the time, the only state prison for women in New York. The project was pioneered by Josephine Shaw Lowell, a progressive reformer who believed that gender-separated, specialized housing was critical to the reform of female delinquents. Lowell maintained that vice could be trained out of vagrant women between the ages of 15 and 30, and advocated a rural cottage living system so that they might be made virtuous by living in a pastoral, family-like environment. However, records and journalism of the day suggest that although the House of Refuge aimed to serve as a safe house, its disciplinary and social practices often resembled those of a prison.

In 1896, a newspaper reporter who was given a tour of the House of Refuge for Women wrote about the institution’s prison building, a 96-cell structure intended for new arrivals and punishment cases. The reporter said, “The prison is naturally the gloomiest building of the Refuge … There are three dark cells in the lower part of the building for the solitary confinement of insubordinate females.”

Estelle Friedman, a noted scholar of women’s prison reform history, describes an 1899 riot because of this harsh treatment in her 1981 book Their Sisters’ Keepers:

Excessive physical punishment provoked a major riot in 1899. An investigation disclosed not only harsh punishment but also complete mismanagement. A new administration closed the dungeon and revised the merit plan but within a year their reports mention punishment cells again.

Newspaper articles from the period also reveal this more disciplinary side of the Refuge’s methods. The local Hudson, NY blog Gossips of Rivertown has detailed some of these newspaper articles reporting on the cases of particular women who were wrongfully imprisoned and faced harsh treatment during their imprisonment.

The documents in the Lillie Patch case file reflect an institution that was used to both protect and punish. Here, included along with the record of conviction, is a form from the date of Lillie’s intake in which she grants permission to “the Superintendent and her assistants to receive, open, read, deliver, destroy, retain, or return any letters addressed to me while here.”

The intake record notes that Patch is “practically illiterate” and her mental capacity “below normal.”

However, other details sprinkled throughout the case file suggest that Lillie could read. Her intake form indicates that she writes to her mother, and a later document notes that she amuses herself “by knitting and reading.” The reason for the disconnect between these facts is unclear. Nonetheless, the varied historical clues in Lillie’s case file emphasize the dominant attitudes towards delinquent young women. This firsthand documentation is a reason Davies recognized the importance of the file and held onto it.

“I thought it was something unique, certainly in some of the language they used, and the description of her behavior,” Davies explained. “This is how they treated women. This is how they treated people with limited abilities. And it’s just such a change. Yet it wasn’t that long ago.”

Written Correspondence

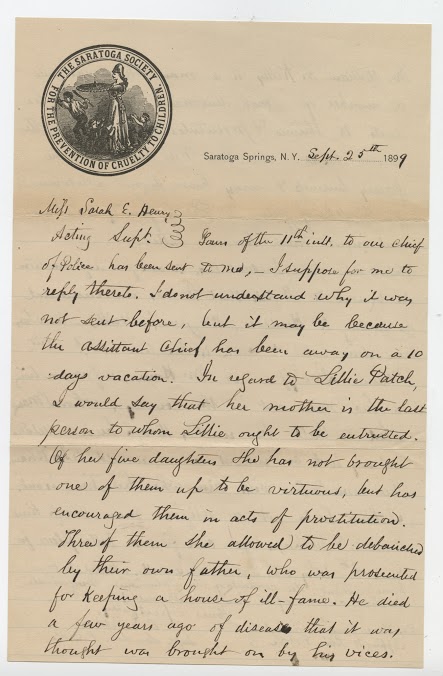

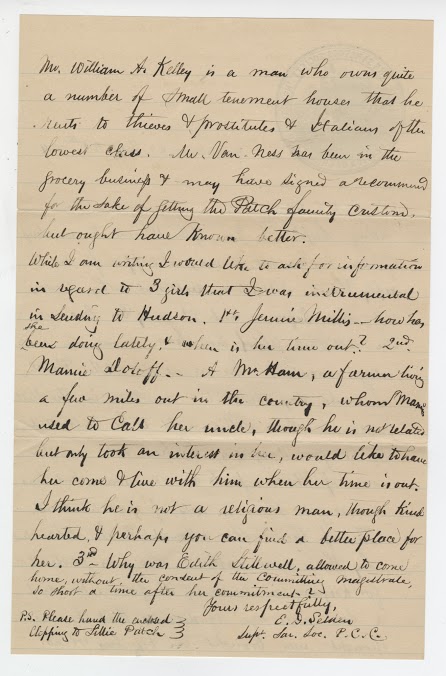

In principle, the House of Refuge shared more features with a safe house or reformatory school than a typical prison. Josephine Shaw Lowell believed that vice in young people was the result of an impoverished environment, and that the best way to reform delinquency was to remove them from that environment. One special aspect of the Lillie Patch case file is that it includes correspondence between the House of Refuge for Women and other reform-based organizations from the period, providing insight into the multifaceted effort to address the problem of impoverished children. The file includes an 1899 letter addressed to Superintendent Sarah E. Henry from the Saratoga Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, which advocated for several Saratoga girls who were kept at the House of Refuge.

The letter is a response to an earlier inquiry from the House of Refuge for Women about the possibility of Lillie’s transfer to her mother’s care. In reply, the Saratoga Society resolutely states, “her mother is the last person to whom Lillie ought to be entrusted.” The Saratoga Society then goes on to describe the depravity of Lillie’s home life, including incest committed by her father and trafficking by her mother. The letter also characterizes the tenement building in which the Patch family lived as a place rented out to “thieves & prostitutes & Italians of the lower class.” The letter writer regrets that the building’s owner, who rented out the apartment to the large Patch family, “ought to have known better.”

A letter from Lillie’s sister was also kept in the file. On July 18, 1901, her sister penned a letter to the Superintendent, expressing her concern that she had not heard from Lillie for a very long time. The letter explains that Lillie had told her mother that she could be reached at an address in Newark, but a letter her mother addressed there was returned unclaimed. Since then, her “mother is dead now and Buried and she said for me to look after her so pleas let me know as soon as Posible.”

It is unclear whether the House of Refuge authorities aided Lillie’s sister in her search, or whether the sisters were able to get in contact. The facility’s right to control the young women’s mail was likely in practice in this case, and the correspondence also demonstrates the limited contact that incarcerated girls had with the outside world, including their own families.

The State Custodial Asylum for Feeble-Minded Women

A likely reason for Lillie’s uncertain whereabouts is that beginning in August 1900, the House of Refuge for Women applied for Lillie’s transfer to the State Custodial Asylum for Feeble-Minded Women in Newark, New York. Established in 1878, the Asylum was also a project of Josephine Shaw Lowell and housed women who were considered promiscuous. She established this institution with the assistance of the State Board of Charities, advocating for the Asylum before the state legislature by arguing that “feeble-minded women often disregarded moral and sexual restraint when placed in the undisciplined environment of an almshouse and frequently had illegitimate children who, in turn, became dependent on the state for their welfare,” and that placement in a specialized institution “prevent them from multiplying their kind.”[3] Documents in Lillie’s file from the State Custodial Asylum include the application, notification of Lillie’s place on the waiting list, and final approval of her transfer. As her record at the House of Refuge ends in January of 1901, it can be assumed that Lillie was successfully transferred to the Asylum. The application in particular reflects prevailing beliefs about delinquency and female sexuality at the turn of the twentieth century.

For example, the application questions focus largely on physical characteristics and deformity. This suggests a link between physical irregularity and mental incapacity, a common attitude from the period. The application reads, “Her face is peculiar and carries her head more than erect.” It describes her crossed eyes and asymmetrical shoulders as deformities in the same breath as it remarks upon her speech impediment and past epileptic fits. Interestingly, the application does not provide much detail of Lillie’s current feeble-mindedness. Questions and answers include:

Any peculiar habits in her case? No

Is she good tempered? Yes

Has she any wanton or destructive habits? No

From these remarks alone, it is difficult to glean any significant disciplinary or behavioral failing on Lillie’s part. Instead, the greatest condemnation is of her former sexual promiscuity. The application refers to her prostitution, syphilis, and childbirth at age 16. As the State Custodial Asylum for Feeble-Minded was intended to treat promiscuous women, it appears that her past transgressions warranted the final conclusion:

The girl is feeble-minded. The only history I can obtain is by questioning the girl herself and her statements cannot be relied upon.

The application to the State Custodial Asylum is stamped “Approved - subject to space.”

Good and Bad Behavior

Besides this wide swath of institutional records and correspondence, the greatest insight into Lillie’s day-to-day life at the House of Refuge for Women is found in her “Record and Report”, which documents her behavior every week from February 1898 to January 1901. In each entry, Lillie is given a score out of 10 for nine different factors, including personal cleanliness, profanity, and honesty. These scores are then translated into a weekly mean, which must average out to at least an 8.7 in order to constitute progress towards completing her five-year sentence. Most weeks, only Lillie’s average is noted, usually a full 10.

On the few circumstances in which she is given a lower score, the number is accompanied by an explanatory note. These include a zero for deportment because she “took a nail out of her window,” a zero in diligence for the simple offense of “lazy,” and other faults in her personal hygiene and honesty. One week features an average of only 2.2 because she feigned sickness, accompanied by a detailed paragraph about the symptoms she pretended to suffer. For the last year of her record, however, Lillie excels, receiving straight 10s before she is transferred to the State Custodial Asylum. The only note jotted down for this period simply reads, “a very good girl.”

[1] This name has been changed to protect the individual’s privacy.

[2] Fox Butterfield, "All God's Children: the Bosket family and the American tradition of violence," (New York: Knopf, 1995), 184.

[3] Thomas Stearns, “Early State Schools of New York,” from Museum of Disability History, 16 November 2011, Web, http://museumofdisability.org/early-state-schools-of-new-york/.

Emma Friedlander is an intern with the Prison Public Memory Project in Hudson, NY focusing on research, story development, community engagement and outreach. She is a rising senior at Grinnell College, where she studies History and Russian. Her work experience includes internships at Macmillan Publishers and the Museum at Eldridge Street in New York City. Emma is also the editor-in-chief of the Grinnell College student newspaper, the Scarlet & Black.