On the Outskirts of Confinement

/The Gatehouse and its Keepers

*By John Mason

In 1918, Irene Butts, a lithe, bespectacled girl with a ready smile and a twinkle in her eye, fresh out of high school, made the big move from Booneville, out near Utica, to Hudson to work as a matron at the New York State Training School for Girls. From 1904 to 1975, the buildings and grounds that are now the Hudson Correctional Facility were the site of the training school, which housed 12-to-15-year-old girls who were regarded as “incorrigible.”

The matrons

“This was a place where young women could get a job,” said Suzanne Tenerowicz of Greenport, the granddaughter of (Bessie) Irene Butts, later Irene Mullins. “It was not a bad job for a woman,” she said. “You didn’t have to be college-educated and you probably ended up a lot better off than girls that worked in factories or what-not.”

One of the bigger buildings on the grounds had dorm rooms for the matrons.

The matrons, said Tenerowicz, weren’t like prison guards but young women closer in age to the girls, who were able to establish relationships on a more personal level with them.

Irene's stint as a matron was apparently a short one. While working there she met and married Michael Mullins.

The young family

Born in 1892 in Hudson, Michael had worked at the training school and the Firemen’s Home before he enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1917 to fight in what was then called the Great War.

On his return stateside, he went back to work at the training school, where he became head of maintenance, a position he held for the next 43 years. And he met Irene.

In 1920 or 1922, the family of three, Michael, Irene and John, moved into the Worth Avenue gatehouse at the training school.

There, Michael and Irene had four more children, Priscilla (Pat), Elizabeth (Chickie), Mary and Jim, all born in the maternity hospital on the grounds of the Girls’ Training School.

Rural life

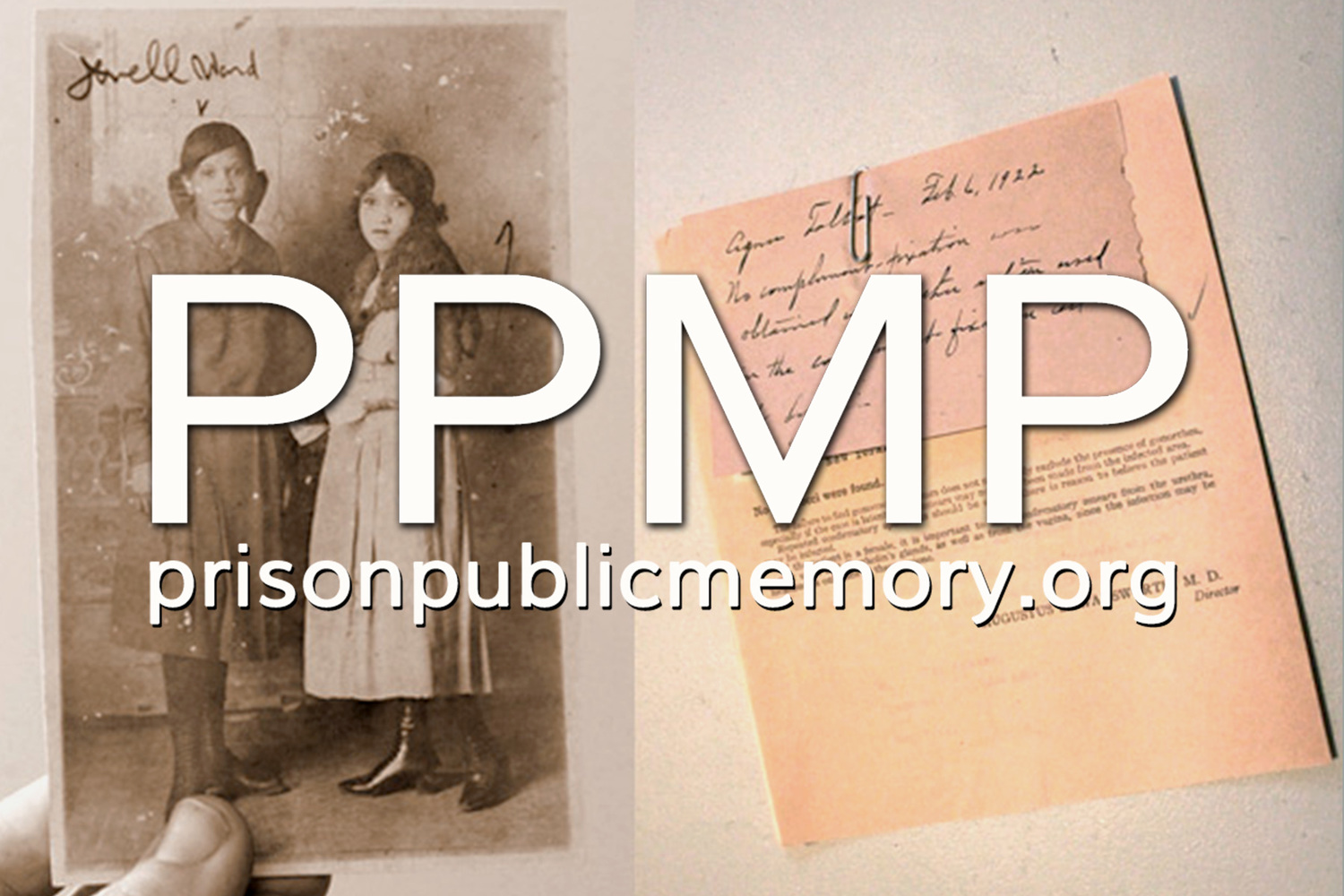

According to the Prison Public Memory Project, “The location of the prison, on 40 acres overlooking the Hudson River, reflected the growing faith of that time in the curative powers of the rural countryside.”

In 1904, the property that had been the House of Refuge for Women — this country’s second reformatory for women — was replaced by the Girls’ Training School. The girls raised food for the school on a vegetable farm as well as a pig farm.

“The idea was to get the kids out of the city,” said Suzanne. The girls of the training school had big gardens, she said. They all dressed in white for the big May Day celebrations, complete with maypoles. It was not uncommon for the girls to come to the Mullins’ house and help with laundry and other chores.

The gatehouse

Suzanne, born in 1953, and her brother Peter, born in 1950, remembered the gatehouse as being enormous when they were young and tiny when they came back as adults.

“One day a few years ago, my aunt got permission for us to go in,” Peter said. “It was so small it was unbelievable. Seven people lived there.”

Michael and the two boys slept in one room on the first floor of the split-level house, Peter was told by his aunt, and Irene and the two girls slept in one room on the upper floor.

Once the five kids had been raised, his grandmother went back to work at the training school, probably as a bookkeeper, Peter said.

Peter and Suzanne both remembered going to their grandparents’ house on Sunday mornings after church.

“We’d go up there and my grandmother had doughnuts on the table for the kids,” Peter recalled. But they were told, “Don’t go down the hill,” where the training school was, added Suzanne.

To the left of the house was a long row of chestnut trees and the kids would gather chestnuts.

“We wandered,” she said. “There was never a fear of anything happening.”

Sundays were also visiting days for the families of the girls.

“I think they had to enter through Worth Avenue,” Peter said.

The iron fence had been built by the Works Progress Administration in the 1930s.

“When people came to visit, my grandfather would yell, ‘Go open the gate,’” said Peter. “There was a huge skeleton key tied to a block of wood hanging on the doorway. I grabbed the key, walking out the door, swinging it, the block of wood is swinging, the chain broke and the block of wood hit me between the eyes. I looked up and the people in the car waiting for me to open the gate were laughing their heads off.”

The girls

The girls came to the school for a variety of reasons.

“(It was) always said they had problems,” said Suzanne. “Some were found on the street drunk or their family was fed up with them. Petty things, shoplifting. I never remember anyone escaping from there, probably because there was nowhere to go.”

Peter recalled, as an altar boy at St. Mary’s, serving mass at the Girls’ Training School’s chapel.

“There were a lot of girls in the church,” he said. “All different races. They appeared pretty young. We didn’t understand why they were there. We kind of kept our distance; we were afraid (of what would happen) if our grandfather caught us.”

Suzanne’s husband, Pete Tenerowicz, worked at Hudson Correctional Facility for 15 years. She feels like they have inside knowledge that has eluded many people around here.

“I talk to people from around here and say, ‘Do you remember the training school?’” she said. “They don’t remember. (A few years ago) I said to someone, ‘Do you know there are 800 prisoners back there?’ They were shocked — out of sight, out of mind.”

***

*Editor's note: This is an edited version of a story that first appeared in The Register Star on March 7, 2015. It appears here with permission from the writer, John Mason. He is a reporter at the Register Star and a Lecturer in English at SUNY Albany. Read the complete article here.