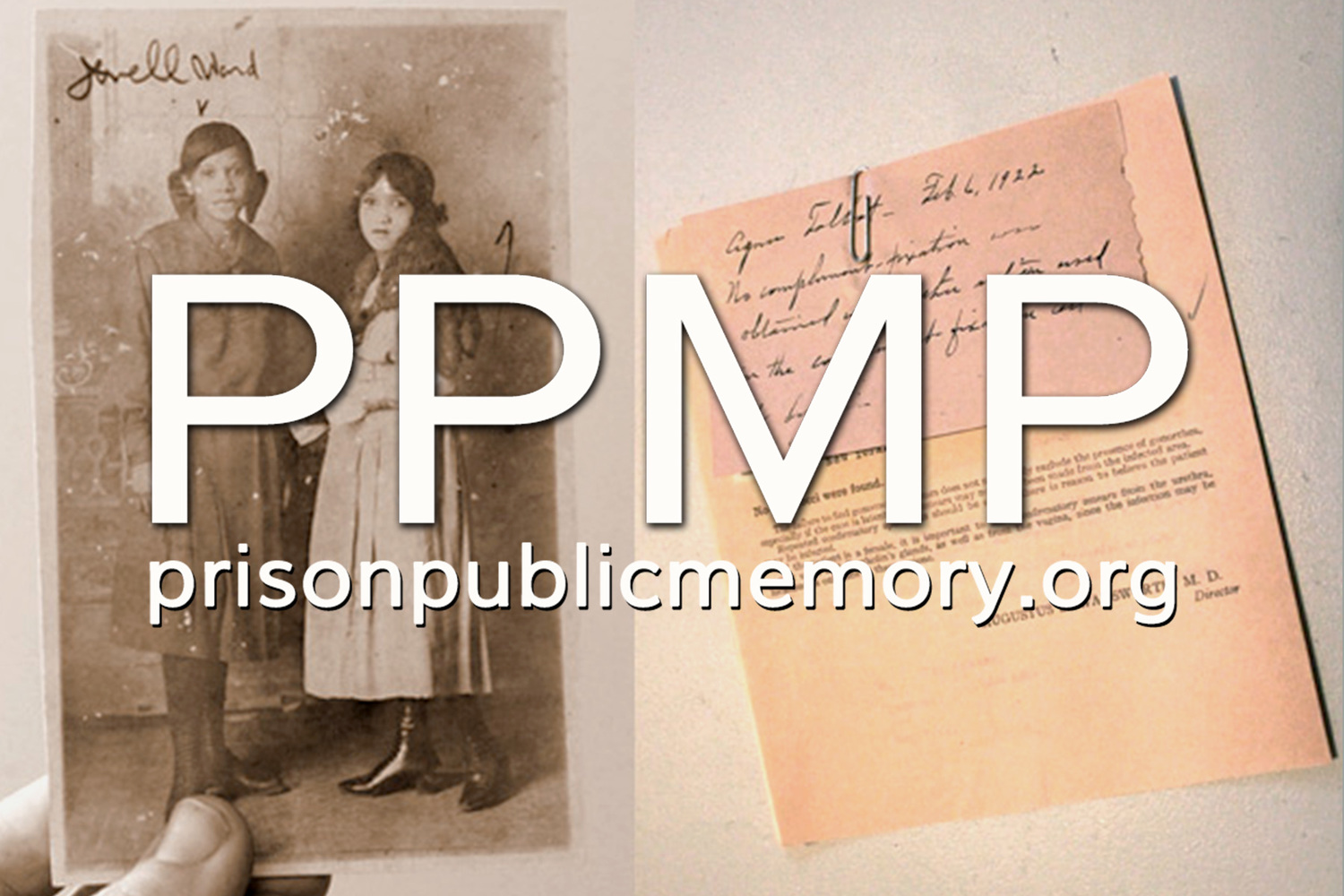

"They Are All Ellas..."

/In an article she wrote for the New York Times in 1996, journalist Nina Bernstein tells the story of famed jazz singer Ella Fitzgerald’s experience at the Training School for Girls in the 1930’s. Here are excerpts from the Times’ article:

ELLA FITZGERALD sang jazz in a voice so pure and perfected that it admitted no pain — and America loved her for it….Yet…for over 60 years she kept the cruelest chapter of her own history a secret: her confinement for more than a year in a reformatory when she was an orphaned teen-ager.

The unwritten story survives in the recollections of former employees of the New York State Training School for Girls at Hudson, N.Y., and in the records of a government investigation undertaken there in 1936, about two years after Miss Fitzgerald left. State investigators reported that black girls, then 88 of 460 residents, were segregated in the two most crowded and dilapidated of the reformatory’s 17 “cottages,” and were routinely beaten by male staff…

Like Miss Fitzgerald, most of the 12- to 16-year-old girls sent to the reform school by the family courts were guilty of nothing more serious than truancy or running away…they were typically victims of poverty, abuse and family disruption…

When Thomas Tunney, the institution’s last superintendent, arrived in 1965 and tried to bring back former residents to talk to the girls of his own day, he learned that Miss Fitzgerald had already rebuffed invitations to return as an honored guest.

“She hated the place,” Mr. Tunney said from his home in Saratoga Springs, where he retired some years after the institution closed in 1976. “She had been held in the basement of one of the cottages once and all but tortured. She was damned if she was going to come back.”

A more generous image of Miss Fitzgerald’s experience there was painted by E. M. O’Rourke, 87, who taught English at the school in the 1930′s and remembers Miss Fitzgerald as a model student. “I can even visualize her handwriting — she was a perfectionist,” she recalled. There was a fine music program at the school, she said, and a locally celebrated institution choir.

But Ella Fitzgerald was not in the choir: it was all white.

“We didn’t know what we were looking at,” Mrs. O’ Rourke said. “We didn’t know she would be the future Ella Fitzgerald.”

She did sing in public at least once while she was at the reformatory, according to Beulah Crank, who later worked as a housemother there. Mrs. Crank, 78, said she was with her parents at the A.M.E. Zion Church in Hudson the day Miss Fitzgerald performed with a few other black girls from the school; she would have been no more than a year away from her legendary victory in a talent contest at Harlem’s Apollo Theater.

“That girl sang her heart out,” Mrs. Crank remembered.

Gloria McFarland, director of psychology at the reformatory from 1955 to 1963, found Miss Fitzgerald’s record in the musty files. “She was a foster care kid when she came,” said Dr. McFarland. “She was paroled to Chick Webb’s band.” Later, the institution’s old juvenile records were destroyed by order of the state.

All her life, Miss Fitzgerald was intensely reluctant to talk about her past. As recently as 1994, when this reporter first stumbled on evidence that she had been at the school, Miss Fitzgerald kept her silence…

If she was almost lost to us, how many like her have been?

“How many Ellas are there?” Mr. Tunney asked. “She turned out to be absolutely one of a kind. But all the other children were human beings, too. In that sense, they are all Ellas.”

For the complete story see “Ward of the State: The Gap in Ella Fitzgerald’s Life”